Different languages

Ways of accommodating different ways of communicating.

In the survey, interviews and workshops done as a part of the i3 project, the challenge of speaking different languages in integrated research projects came up many times.

There are at least two causes of this sense of people speaking different languages:

- Using disciplinary jargon

- Talking past each other.

The first, although more obvious in a team, is probably easier to deal with.

Using jargon

This is using technical words or phrases that are not known or understood by others, or where the same words are used by different people to mean different things. It happens a lot, and can be especially noticeable in integrated research teams, for example between social and biophysical sciences, western science and Mātauranga Māori and between scientists and stakeholders.

At the start of a project, this issue needs to be raised and discussed to everyone is made aware of it.

As a team you can agree to either:

- decide to thrash out all of your differences at the start and agree on the vocabulary that you are going to use, or

- get started and be aware of the differences that might arise in the course of the project.

The advantage of the former is that you have established a common vocabulary in your team. This takes time and diminish momentum. Also, you are unlikely to know where terminology differences might be at the outset. Also, if the focus changes over the course of the project the definitions of words that you have developed may become less relevant. A further disadvantage is that you may end up with a ‘translation gap’ between your team and the rest of the world.

The advantage of the latter is that you don’t invest the time upfront. The disadvantage is that you will need to be more aware of potential differences during the course of the project and be prepared to stop and translate. If everyone is made aware of this issue at the outset, they can be alert to it.

Talking past each other

This is where two or more people talk about different subjects, while believing that they are talking about the same thing. In some ways this is more problematic than the use of jargon, because it can go unrecognised.

Tips for managing different languages:

- Be conscious of disciplinary words, concepts etc that you are using.

- Where you can, use plain language, and explain the use of disciplinary terms.

Regularly check in to see if people are understanding each other. A good way when someone is talking to me, I say “Let me try and explain that back to you to see if I understand what you mean”. This means that you need to be able to re-explain what you heard in your own words. The other person can then see if you are following them.

Be curious. Ask questions like “what do you understand by ‘XYZ’?”

Recognise that often people talk about things that don’t seem important to you because they see things differently, and consider different things important. Exercises like the “What sort of researcher are you” can help appreciate these differences in a team.

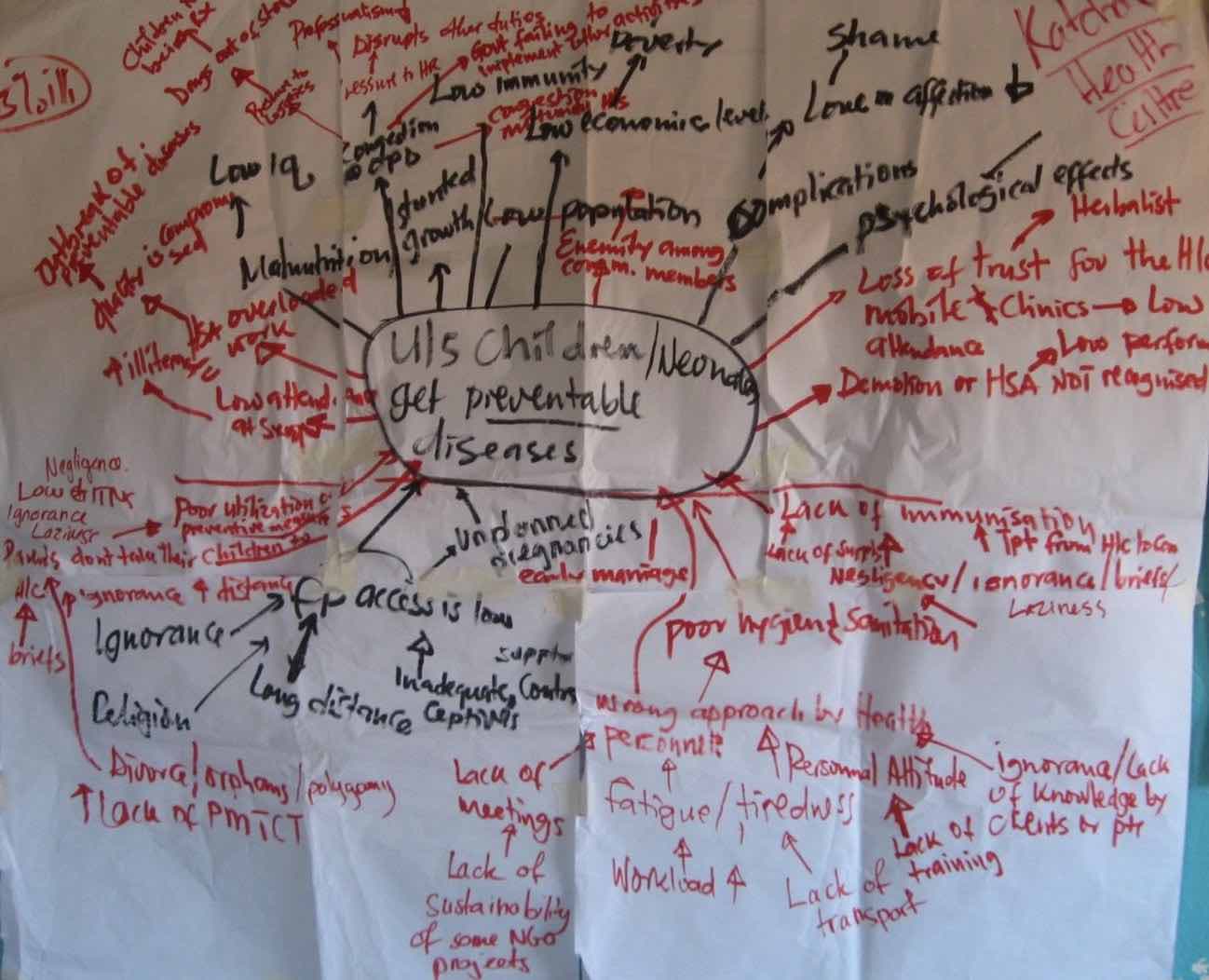

Doing exercises jointly, like problem trees or systems mapping, can really help identify where you are talking at crossed purposes.

Pay attention to how you have conversations, and especially how you listen. This sounds trivial, but it isn’t. Here are two useful resources for that:

More information

10 ways to have a better conversation, Celeste Headlee, TEDx talk

Why You’re Talking Past Each Other, and How to Stop, Harvard Business Review