Anti-rules for research impact

Learning from 'what not to do' in making your research useful.

A 'how not to' by Lewis Atkinson from the Integration and Implementation Insights blog.

This series of 12 insights tell us what not to do if we want our research to have an impact. They are written as tongue-in-cheek anti-rules, but are a good way to reflect on what we do in our own research projects.

Design

1. Only focus on your part of the problem

Avoid seeing the problem as a whole to limit the intervention possibilities. Acknowledge the translational “gap” but be ambivalent about who owns it. Contest it with others and perpetuate confusion with a range of definitions for what research translation means.

2. Ignore the complexity of multiple interacting conditions

Avoid paying attention to ‘agency’ at the heart of individual and/or population behaviour, where different people and groups seek their own desired outcomes. Instead maintain that yours can be the ONLY outcome and therefore confine discussion of strategies and plans to a small circle of trusted advisors. Announce big decisions in full-blown form. This ensures that no one will start anything new because they never know what new orders will be coming down from the top.

3. We Already Know Everything (WAKE)

Be suspicious of any new idea from below — because it’s new, and because it’s from below. After all, if the idea were any good, we at the top would have thought of it already. Above all, never forget that we got to the top because we already know everything there is to know about this.

Doing

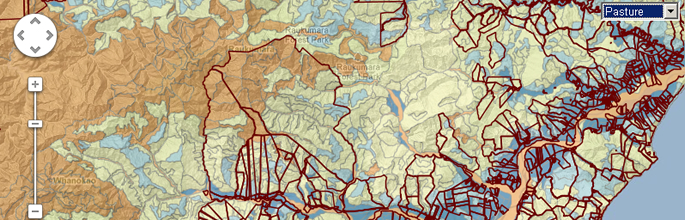

4. Close off the flow of information and knowledge

Keep a tight lid on who is involved and what knowledge is seen to be relevant. Do not share your data or allow access to your sources of data. Minimise the rate of data exchange within and among various research and non-research partners.

5. Maintain impermeable professional institutional research boundaries

Reinforce the divisions between researchers and maintain competitive silos in the research sector driven by institutional rivalry, specialist societies and professional associations. In the name of research excellence, encourage cut-throat competition. Get groups to critique and challenge each other’s proposals, preferably in public forums, and then declare winners and losers.

6. Build your immunity to change

Protect yourself against the nuisance of change. Maintain strict hierarchy and blame problems on the incompetent people below — their weak skills and poor work ethic. Complain frequently about the low quality of the talent pool today.

7. Focus on the means, not the ends

Make the process of accessing funds and undertaking the research project and translation of results as difficult and complex as possible. Keep everyone very busy and skew the loading of incentives towards furthering their own personal ambitions rather than awareness of the impact of actions on others, unintended or otherwise.

Dissemination

8. Ignore the changing needs of communities you serve

Advocate that “research translation” is something new and mysterious. That it is driven by research needs as primary inputs rather than the impact on the communities that researchers are generating findings to serve. Argue that research translation can’t be done as part of the normal scope of day-to-day practice and that it cannot be changed once it is in progress.

9. Avoid any measures of effectiveness or accountability for translation

Translation is someone else’s problem. Make sure that all researchers are part-time and without clear accountability and diffused responsibility for impact. Better still, practice public humiliation, making expectations for translation ambivalent and impossible to achieve. Everyone will know that risk-taking is bad.

10. Maintain that translation is a linear process

Maintain your commitment to the unidirectional view of translation. Neglect the value added that broader thinking about the problem and intervention can bring, including the advantages of multidisciplinarity to basic science and technology development.

11. Maintain a myopic internally focused view

Do not scan the literature for any lessons about research translation because we are different and successful research translation can only be done based on research done by our people in our context.

Evaluation

12. Track everything that can be tracked and ask for it as often as possible

Create complex structures, processes and reporting systems. Insist that all procedures be followed. Encourage researchers to find answers as soon as possible and at least cost. Favour exact plans and guarantees of success. Don’t credit people with exceeding their targets because that would just undermine planning.

For more information, see read Twelve ways to kill research translation.